This natural interest in ourselves means that the robots in the exhibition hold up a mirror to us. Two of the more modern robots are the Kodomoroid, a Japanese robot used for reading weather reports, and the Robothespian. Both of them are very modern creations, but the Komodroid is almost too lifelike. In contrast, the Robothespian has its insides on display. It’s not trying to suspend your disbelief that you’re looking at a real person, and that arguably makes it easier to relate to, despite the fact that it’s very obviously not a human.

Ben thinks this indicates a bit of an identity crisis – if the things that make us uniquely human are being taken away from us, is it time for the robots to take a step back?

The word ‘robot’ didn’t exist until the 1920s, but the things themselves have been around a lot longer than that. The robots in the exhibition are all products of their time. The earliest are simple wooden figures that re-enact scenes from the Bible, to show an illiterate public the meaning of the crucifixion.

These animated scenes eventually spread into the homes of the wealthy and to exhibitions of curiosity for the paying public.

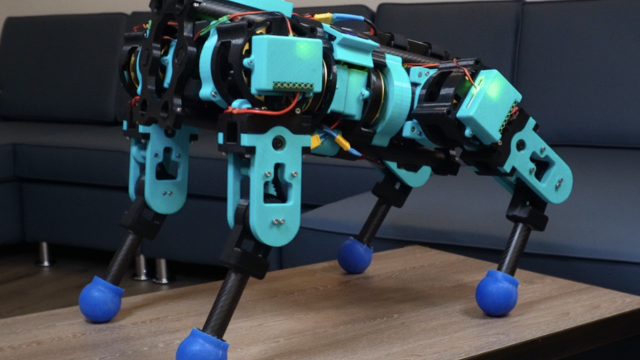

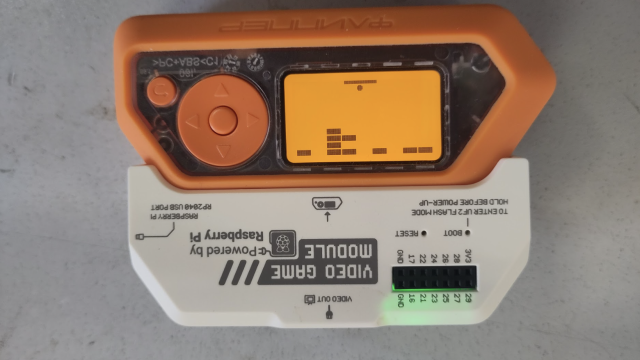

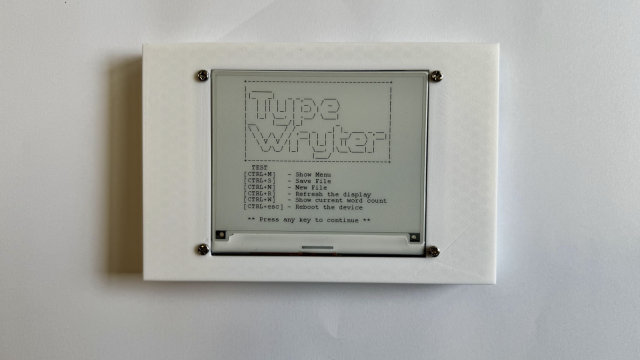

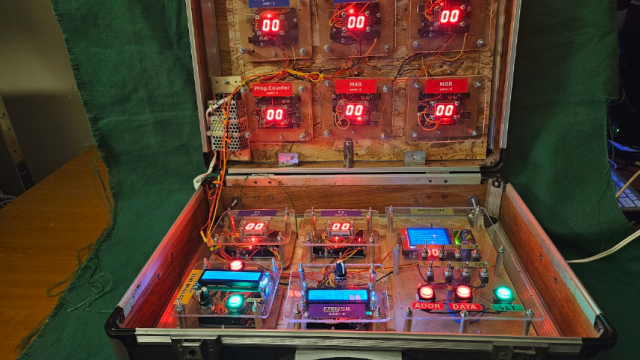

Machines in this age could write, play music, and produce woodwork but, without Arduino and Raspberry Pis, they were still very much single-use creations, with no intelligence. We’re extremely fortunate that whatever we make today can be repurposed with a few lines of code.

But it’s not until the age of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis that we start to see the mechanical humans that came to define the word ‘robot’ for most people. These are the classic science-fiction robots, which can mimic actions programmed into them by a human. Where it gets exciting is the point at which the robots go from mimicking the actions of the body to those of the mind. But how comfortable are we with having an intelligent mechanical servant? It’s odd enough to issue commands to an Alexa, or something similar, without saying please; it’s going to be weirder still when Alexa has a face.

Ben is optimistic about the rise of the robots. “Pepper, the robot created by SoftBank, is one of the first to cross the uncanny valley, the gap created when robots get a little too close to us for comfort,” he says. “It’s friendly. It can give you a fist bump and truly interact with you.

“99-point-something percent of all robots are not humanoid; they’re designed to do a specific job. But, when they do finally escape from the factory into the human world, will it be helpful for them to have a human form? Where we go next is the big question. Let’s see what happens.”

Robots: 500 years in the making is on at the Museum of Science and Industry until 15 April 2018. After that, it’s going to the National Museum of Scotland, the Life Science Centre in Newcastle, and will then go on a world tour until 2021, including Stockholm and Tokyo.