“One of the things I like is that we still refer people to the makerspace as well. If a potential client comes to us with an idea, we will sometimes say, ‘You don’t want to spend loads and loads of money with us, but if you go to the makerspace, there will be someone there who can support you while you start off.’ It’s a supportive community, and it doesn’t cost very much to join.

CLIENT WORK

“Everything we do is tailored to the client. We don’t particularly invent things. We have one project, Push to Talk, which is our in-house product that we’re developing with Liverpool City Council as part of the Council’s 5G project, and that’s going out to people’s homes.

“The Environment Agency project that we’re working on is a live level sensor. Because of the way the Environment Agency monitors its rivers, they have a big base station where you can see at that particular point what the level is, but you don’t necessarily know what the water level is like ten miles down the river, because there isn’t any data being gathered until the next base station.

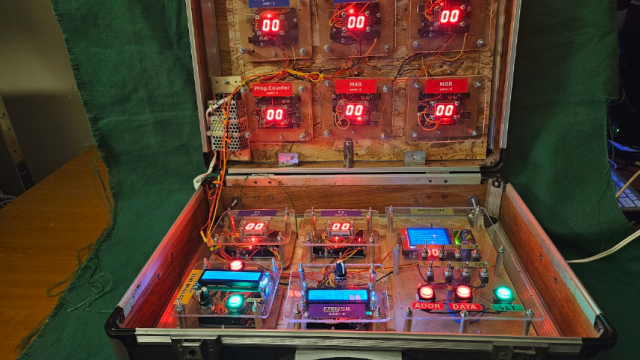

“They wanted us to develop some smaller sensors that they could tap into, through which they could monitor the water levels along the length of rivers. We’ve been using a new technology called NB-IoT (Narrowband IoT ), which is a bit like LoRaWAN signal. We started developing that while we were at DoES, and we’ve done various different versions of it. We’ve also created some bespoke sensor hardware for them, so that they can train their staff on how to use these small devices so that they can get the data they want out of those sensors. We’ve done quite a lot of work with the Environment Agency, including a national training scheme for these devices.

“We’re currently at a staff level of five. We do a lot of stuff for how small we are. This week we’re just finishing off a build for the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford. We’re putting together all the interactive side of four lunar landing exhibits. You touch something and then it lights up and plays video, or you put an RFID tag on something and it plays audio into a specific space. We do all the electronic side of that.

“Patrick’s a design engineer; his degree was in automotive engineering and structures, and he’s migrated into this field of electronics. My background is in textile design; I do a lot of the creative design.

"Made Invaders, for example is my design, and then Patrick works on how to make it function. I don’t know much about the electronics, but I do know what they should look like: the design rigour that needs to go into things. We have quite a nice partnership of skills.

“We’ve got a product designer now who does all the CAD for us and makes everything look good. It’s nice to have people to support us. When it was just the two of us, Patrick was doing the electronics and the software, and we’ve now got a software engineer and a product engineer as well.

“Gradually, we just built up and built up. We’re doing much bigger projects now, still working with the Environment Agency. We didn’t go to the makerspace to design a product to then start a business out of it; we’ve formed a business within the makerspace, providing a complementary skill to some of the other people that were there. We’ve grown from there over the last five years. It’s been serendipitous.

“A lot of it’s been driven by Patrick and his interest in new problems. One of the things that stands out for us, as a business, is that we’re willing to take a punt with a client. Even if we don’t know how something works, we know that it must be possible. Whereas we know that a lot of businesses, unless it fits into their formula, they won’t be willing to take it on. It comes back to the time when we wanted a prototype – there was no-one who was willing to do a proof of concept, or a prototype. ‘No, we don’t want to make one of something; if you want 10,000, come back.’

“I think our biggest run has been 200 things for a client. If you go to somewhere that’s got the big pick-and-place machines, and ask them to make you 200 of something, they’ll tell you it’s not worth their time to set up the machines to do that. We can manufacture things in small runs that big places just don’t want to do. It’s almost like the bigger the company, the less likely they are to want to deal with you. We try to fill that void.”